It has always struck me that our models for managing change, while logically sound, often feel sterile and disconnected from the messy reality of human psychology. We follow the steps, create the plans, and communicate the vision, yet so often, transformation fails to take root. I contend this is because most frameworks overlook two fundamental, intertwined issues. The first is the primordial role of awareness as a prerequisite for action. The second is our collective inability to navigate the discomfort of genuine complexity.

Hypothesis One: The Unseen Barrier of Awareness

My first contention is that all meaningful change, whether personal or collective, is predicated on a shift in awareness. One must first be able to see that there is a problem to be solved. More crucially, this awareness must evolve from a narrow, individualistic frame to a broader, systemic one. Until a certain threshold of understanding is reached, any action taken is likely to be superficial or even counterproductive.

We see this play out on a global stage. Consider powerful billionaires who, while perhaps intending to solve discrete problems, operate with a partial view. Their focus on individual gain or technologically optimistic siloes, often coupled with what one might describe as sociopathic personality traits, prevents them from addressing issues in a way that benefits the whole system. They are not solving for humanity; they are solving for their own paradigm. At a smaller scale, this is the shareholder mindset that paralyses company management. They are aware of the need for profit but blind to the longer-term necessity of preserving the business itself, the workforce, and the social licence to operate. The primary issue is not a lack of solutions, but a lack of the right kind of awareness to orient those solutions towards a systemic framework.

Validation and Deepening

This perspective finds robust support in advanced leadership theory. The work of Otto Scharmer and his Theory U, developed at MIT, positions this blind spot as the central failure of contemporary leadership. The journey begins with what he calls ‘downloading’, where we operate from entrenched patterns and mental models. The shift to transformative action is impossible without first moving through the stages of ‘seeing’ and ‘sensing’, which require us to suspend judgement and observe the system as it truly is, beyond our own filters. This is the very essence of cultivating awareness.

Furthermore, the work of adult developmental psychologist Robert Kegan provides a stunningly accurate map for this problem. He explains that we are ‘subject’ to our mental models, meaning they are invisible to us and control our thinking. A leader with a ‘socialised mind’ is subject to their tribe’s expectations, such as quarterly returns for shareholders. A leader with a ‘self-authoring mind’ can create their own framework, but it often remains individualistic and ideological. It is only at the later ‘self-transforming’ stage that one becomes aware of the limitations of any single framework and can hold multiple perspectives to seek systemic, interdependent solutions. The awareness I am pointing to is not just a nice to have; it is a developmental achievement.

A Necessary Challenge

However, to rely solely on the internal cultivation of awareness is perhaps too idealistic. One could challenge this by pointing to the power of structural catalysts. Sometimes, awareness is forced upon us by external events. A corporate crisis, a new regulation, or a sharp decline in market share can create a sudden and unavoidable ‘sense of urgency’, as in John Kotter’s change model. In these cases, action in the form of a new rule or a market shock precedes the deep awareness. The awareness follows the change in the system’s conditions, suggesting that while awareness is crucial, it can be triggered by mechanisms beyond introspection.

Hypothesis Two: The Fallacy of Control in Complex Domains

My second contention is that once a problem is identified, our ability to solve it depends entirely on which complexity domain it resides in, using the Cynefin framework created by Dave Snowden as a reference. We have become exceptionally proficient at managing change in ‘known’ environments, where problems are complicated but have discoverable, expert-driven solutions. This is the world of most corporate change manuals. Yet I find a deafening silence on how to operate in the ‘complex’ domain, where cause and effect are not linearly related and no apparent path exists.

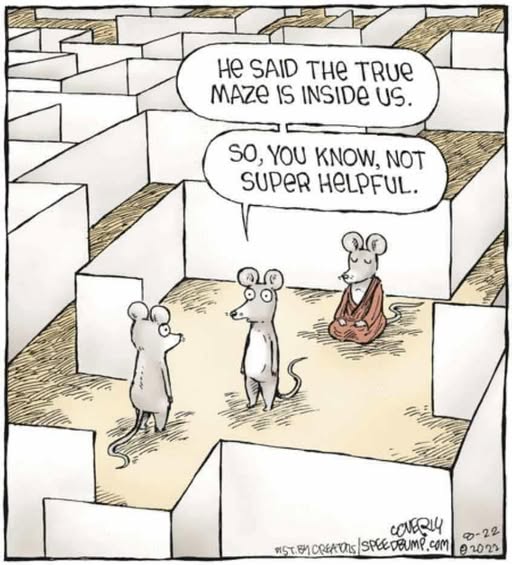

On a personal level, this is the agony of knowing you have a deep-seated issue, perhaps a relational pattern or a psychological block, but finding a solution feels impossible because there is no clear manual to follow. At a collective level, this vacuum of certainty is often filled by those most uncomfortable with ambiguity. They ‘kidnap’ the solution, pushing to implement anything, any familiar but ill-fitting template, simply to escape the discomfort of not knowing. This is how complicated, technical solutions are violently applied to complex, adaptive problems, guaranteeing their failure.

Validation and Deepening

The Cynefin framework exists precisely to prevent this category error. It states unequivocally that the methods for the ordered domains of Clear and Complicated are catastrophic when applied to the Complex domain. The complex domain is defined by emergence and unpredictability; the relationship between cause and effect can only be perceived in retrospect. The correct approach is not to ‘analyse and plan’ but to ‘probe, sense, and respond’. This means running safe-to-fail experiments, observing what emerges, and adapting accordingly. The path does not exist beforehand; it is revealed through our iterative actions.

This aligns perfectly with Ronald Heifetz’s distinction between technical and adaptive challenges. Technical challenges have known solutions that existing expertise can solve. Adaptive challenges, however, require people to change their values, beliefs, and behaviours. The solution is unknown. Our failure, Heifetz argues, is our relentless tendency to apply technical remedies to adaptive challenges. This is the formal name for the ‘solution kidnapping’ I described, where the comfort of a known process is chosen over the difficult work of genuine adaptation.

A Necessary Challenge

Yet, living in perpetual emergence is not a practical strategy for human systems. The challenge to this hypothesis is that people need scaffolding. While there is no predefined path, we cannot function in pure chaos. The art of leadership in complexity is therefore to create containers for the emergent process. This involves setting a clear direction, if not a precise destination, and establishing minimum constraints, a few simple rules that guide experimentation. It also requires creating a safe enough space for people to learn from failed probes without blame. The leader’s role shifts from a solution-provider to a sense-maker, helping the collective narrate the learnings and build a tolerance for the uncertainty that is an inherent part of the journey.

Synthesis: The Indivisible Dilemma

In conclusion, these two hypotheses are not separate critiques but two sides of the same coin. The first highlights the necessary internal condition for change, while the second describes the necessary external method.

The cultivated awareness from Hypothesis One is what allows us to correctly categorise a problem as complex in the first place, rather than forcing it into a familiar but incorrect box. Conversely, the practice of navigating complexity from Hypothesis Two requires a level of personal and collective maturity, a tolerance for uncertainty and a humility that is only possible with the deep awareness described in Hypothesis One.

Our most profound failure in change management is not a failure of process, but a failure of consciousness. We attempt to solve systemic, adaptive challenges with the mindsets and tools designed for ordered, complicated ones. Until we prioritise the cultivation of awareness and the courage to dwell in the messy, emergent space of complexity, our efforts at transformation will continue to fall short, addressing only the symptoms of our problems while their roots remain untouched.

Key Thinkers Referenced: Otto Scharmer (Theory U), Robert Kegan (Adult Developmental Psychology), Dave Snowden (Cynefin Framework), Ronald Heifetz (Adaptive Leadership), John Kotter (Change Management).

#ChangeManagement #Leadership #Complexity #Cynefin #TheoryU #AdaptiveLeadership #SystemsThinking #OrganisationalPsychology #BusinessTransformation #ConsciousLeadership